Ask Professor Puzzler

Do you have a question you would like to ask Professor Puzzler? Click here to ask your question!

A visitor for the US asks the following question: "Who is the father of light?"

"Father of Lights" (note that I'm using the plural of "light") is a phrase which is found in the Bible, and is used to describe God. The reference, in case you want to know, is James 1:17, which reads as follows (using the King James translation):

Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, and cometh down from the Father of lights, with whom is no variableness, neither shadow of turning.

Reading this in a modern translation (New International Version):

Every good and perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of the heavenly lights, who does not change like shifting shadows.

What does the phrase mean? Well, that's a good question! And there are a few ways to take meaning from the title.

- It is a reference to creation; God as the creator of all the heavenly lights, is referred to as the father of them. In a sense, then, you could give Him the title "Star Father."

- It is a reference to Jesus, who called himself "the light of the world." Following the logic of that; if Jesus is the light, and God is his father, then God is the "Father of Light."

- Light, in the Bible, is usually associated with either knowledge or righteousness (or both). For example, Isaiah 9:2 says that "the people who walked in darkness have seen a great light," and according to one Bible dictionary, the word "darkness" there metaphorically means one of the following: misery, destruction, death, ignorance, sorrow, or wickedness. Thus, of course, light would be, metaphorically, the opposite. So saying "Father of Light" could be the equivalent of "Father of Knowledge" or "Father of Righteousness."

The conclusion of the verse, which says he is unchanging, and has no shifting shadows, may be a reference to the stars, which twinkle and shift - indicating that God is greater than the stars of the heavens.

Thanks for asking, and I hope that was helpful!

Professor Puzzler

Judah asks: "A Highly Composite number is a number that has more factors than any other less than it (positive, whole numbers). Like 12 has 6 factors, which is more than any other below it (whereas 1 has 1 , 2 has 2, and so on). Is there an equation to tell if a number is highly composite? If no, than I might find one. :P But is there?"

Hi Judah,

I'm not familiar with an actual formula that you could use (something along the lines of a function that you plug n into it and you get the nth highly composite number out). However, there are some tips I can give you for finding highly composite numbers (short of looking up a list on a website somewhere).

First, it's important to note that what really matters in highly composite numbers is the exponents in their prime factorization. Why? Because the number of factors a number has can be directly calculated from those exponents. Let me show you how.

Take the number 72. How many factors does this number have? We can find out by simply testing numbers to find out if they're factors:

1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 12, 18, 24, 36, 72

72 has twelve factors.

But there's another way to find out how many factors 72 has. Write the prime factorization of 72:

72 = 2332

Now consider the fact that every factor of 72 contains both powers of 2 and powers of 3. For example, 12 = 2231, 18 = 2·32. This is also true of 1, though you might not think so at first: 1 = 2030. Similiarly, 8 = 2330.

But, of course, if a number has 24 or 33 as part of its prime factoriztion, the number can't be a factor of 72, because it has too many twos, or too many threes.

We can look at it this way: if a number is a factor of 72, it contains in its prime factorization either 20, 21, 22, or 23. Similarly, the prime factorization contains 30, 31, or 32.

There are 4 ways to choose how many twos to include, and 3 ways to choose how many threes to include to build a factor of 72. If you've studied counting principles at all, you know that the total number of ways to create a factor is then 4 x 3 = 12, which matches the number we obtained by listing factors.

Let's try another example: How many factors does 6,615 have? I'm sure you don't want to try to list them all by hand, right? So let's try our other method. Prime factorization of 6615 = 335172.

Thus, there are 4 ways to choose how many threes, 2 ways to choose how many fives, and 3 ways to choose how many sevens to include in a factor. Therefore, there are 4 x 2 x 3 = 24 factors.

So how do we use this to help us find highly composite numbers? Well, we can use it indirectly, because we can use this to help find the smallest number that has n factors.

Let's say we want to find the smallest number with 15 factors. Well, 15 can be factored in two ways:

15 = 15 x 1

15 = 3 x 5

Using the first factorization is going to result in a ridiculously large number (21430), so should use the other way of factoring. We need to have a prime factorization that includes an exponent of 2 and an exponent of 4 (2 is one less than 3, and 4 is one less than 5). We'll get our smallest number by assigning the largest exponent to the smallest prime factor, which gives us 2432 = 144. 144 is the smallest number with 15 factors.

What if we wanted to find the smallest number with 16 factors? There are many more possibilities here, because 16 can be factored in several different ways:

16 = 16 x 1 16 = 8 x 2 16 = 4 x 4 16 = 4 x 2 x 2 16 = 2 x 2 x 2 x 2

Each of these gives rise to a different number:

16 = 16 x 1 21530 = 32768 16 = 8 x 2 2731 = 384 16 = 4 x 4 2333 = 216 16 = 4 x 2 x 2 233151 = 120 16 = 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 21315171 = 210

Of these 120 is the smallest, so 120 is the smallest number with 16 factors.

Notice that the smallest number with 16 factors is actually smaller than the smallest number with 15 factors, which means there is no highly composite number with 15 factors. You can't assume that 120 is a highly composite number, either, until you've done some more testing, but if I had to make a guess, I'd say it probably is. Okay, I just checked a list on Wikipedia, and 120 is a highly composite number.

Hopefully this will inspire you to more exploration, and maybe you'll find that formula you were looking for. Thanks for asking!

Esther from Georgia wants to know "Why do extraneous solutions happen in math problems?"

Extraneous solutions are solutions which are obtained algebraically, but even though they are found algebraically, they don't work in the context of the problem. Here are some of the reasons a problem might have extraneous solutions. For each reason, I'll give an example.

Real World Restrictions

Sometimes a solution that we find algebraically is extraneous because it doesn't fit real world restrictions on the solution. For example, consider the following problem:

A rectangle's length is 2 more than its width. Its area is 48 square feet. What is the rectangle's width?

To solve this, we say, let w equal the width. Then we have: w(w + 2) = 48

This is a quadratic equation: w2 + 2w - 48 = 0, which leads to w = 6 or w = -8. However, the real world restriction on the solution is that w is the width of a rectangle, and rectangles can't have negative side lengths. Therefore, -8 is an extraneous solution.

Problem Restrictions

In other cases, the problem itself might set restrictions on the solution.

Find all two digit numbers such that when the number is squared, and ten times the number is subtracted, the result is 11.

This problem leads to the quadratic: x2 - 10x - 11 = 0

(x - 11)(x + 1) = 0

x = 11 or x = -1.

But the problem itself sets the restriction that x must be a two digit number, so x = -1 is extraneous.

Division By Zero

Sometimes a problem has fractions, and a number that works out algebraically actually causes a division by zero, which is illegal, immoral, and socially unacceptable. As a problem writer for math competitions, I like to deliberately create problems in which this happens, because the very best students check their solutions and realize they've got an extraneous solution. Here's a very simple example:

(x + 1)/(x - 1) = 2/(x - 1)

An easy way to solve this is to multiply both sides by (x - 1), which gives x + 1 = 2, or x = 1. But the process of multiplying by (x - 1) has made a fundamental change to the problem; we no longer have a denominator. If we go back to the original problem and try to plug x = 1 into it, we find that we have a division by zero, and therefore x = 1 doesn't actually work; it's extraneous.

Principle Roots

Each positive number has two real square roots. For example, the square roots of 4 are 2 and -2. However, when we write radical notation, we are, be definition, referring to the principle square root, which is the positive value. Thus, a solution may be extraneous because it results from using a negative square root instead of the principle square root. Here's an example:

√(x) = x - 6

To solve this, we square both sides:

x = x2 - 12x + 36

Rearrange, simplify, factor, solve:

x2 - 13x + 36 = 0

(x - 9)(x - 4) = 0

x = 9 or x = 4

Now, plug 9 into the original equation, and you'll see that it does work. But what happens when you plug in 4? You get a false equation! But why does that happen? Because on the left-hand side, 4 has two square roots, and one of them (-2) does work. So it's our own choice to define √(x) as the positive square root of x that results in the extraneous solution.

Are there other causes for extraneous solutions? Probably, but that should serve as a simple crash course on the common ones you'll see in an algebra class.

I'm Glad I've Got a Proofreader

In addition to occasionally writing math problems for this website, I've also written math problems for several states' math competitions. When I sit down to write problems, it's usually because I have to crank out a set of 100 math problems for a competition somewhere. When I'm finished writing them, I send them off to my proofreader. When he's proofreading, what do you suppose he's most likely to find?

- spelling mistakes

- grammar mistakes

- arithmetic errors

- algebraic errors

- ambiguity errors

He does occasionally find spelling/grammar mistakes, but those are fairly infrequent. And yes, I do occasionally have arithmetic/algebraic errors! (When I'm writing a problem, sometimes I have to try two of three different things to make the problem work out correctly, and then I forget which things I've changed, and use numbers from the first version of the problem, and then my proofreader says, "Where in the world does this number come from?")

But the most common issue he finds is an ambiguity issue. Ambiguity simply means that students could reasonably interpret the problem in more than one way. If the student could interpret the problem in multiple ways, then it's a bad problem!

Here's a simple example:

In a right triangle, the sides are 5, x, and x + 1. Find the length of the hypotenuse.

Why is this ambiguous? Because I've implied that there's one answer ("find the length" instead of "find all possible lengths") but there are two possible answers, because the hypotenuse could be 5 (if x and x + 1 are less than 5) or it could be x + 1 (if x + 1 is greater than 5).

Here's another example:

Find the next term in this sequence: 5, 10, 15, ...

The obvious answer is 20, but that's not the only possibility; someone who is familiar with Fibonacci sequences could argue that this is the beginning of a Fib, and therefore the next term is 10 + 15 = 25.

These are just simple examples. The more complicated a problem is, the more likely it is to introduce something ambiguous without meaning to. So I'm glad I've got a problem proofreader.

The Internet Has No Proofreader

Now I put on my other hat - the "Professor Puzzler" hat. On any given day, this blog is a pretty quiet corner of the internet. This blog usually gets just a few hundred visitors per day. (Except on days we publish a new post, then the visitor rate climbs a bit).

But every once in awhile, something goes crazy. Back in February, for instance, there was one day where the traffic to the Professor Puzzler blog was 100 times it's normal rate. We had over 25 thousand page views on just one page of the blog.

Whenever this happens, it's invariably because someone posted an ambiguous (bad) math problem on the internet, and someone linked to our explanation of why it can't be solved.

And I realized something, after the most recent one: the majority of math problems posted on social media are ambiguous. The internet has no proofreader.

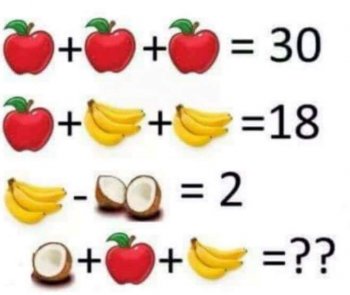

If you're interested to see some of the ambiguous/bad problems we've talked about in this blog, here are links to some of them. Just click on the image to jump to the corresponding blog post.

The most recent one was "The Flower Problem" or (as one site called it) "Pollen Pandemonium." This problem is straight-up ambiguous (and no, it was not part of a kindergarten exam in China; give the Chinese some credit, will you?). The most appropriate interpretation is to say that each distinct flower image represents a different variable. If that's the case, you have a system of three equations in four unknowns, which is unsolvable. If you operate from the assumption that the problem must have a solution, you reject the most appropriate interpretation, and then there is no way to solve it without making an assumption about what the writer intended. Each assumption will lead you to an answer, but depending on the assumption you make, you'll get a different answer. So the internet is full of people arguing for their interpretation, when the reality is, every solution is based on an unwarranted assumption.

The square problem is also ambiguous in the same way that my sequence problem above is ambiguous; there are multiple ways of interpreting the intent of the problem writer, and there isn't one right answer; there are many possible answers. But the problem is great for click-bait sites, because people will spend all day arguing their answer in the comments.

And there you have it: a history of bad math problems on the Ask Professor Puzzler blog. Click-bait sites love problems like this, because they generate arguments, and arguments turn into page views, comments, likes, and notoriety.

Math teachers, on the other hand, hate them...except as teaching tools about ambiguity!

Update June 20, 2016: One wise commenter responded to this blog post by saying "So people would rather argue, pretending unsolvable problems are solvable, than accept the simple fact that the problem was badly phrased to begin with. Seems this could have applications to Internet interactions far beyond the math realm!"

Can't argue with that!

"I noticed that all the perfect squares are either a multiple of 4, or they're one more than a multiple of 4. Is that a rule or something?" ~Wes in South Dakota

Wes, I don't know if it's a rule, exactly, but it's definitely a true statement. Every perfect square is either a multiple of four, or one more than a multiple of four. Would you like me to prove it?

Every integer is either even or odd. That means it's either a multiple of two, or it isn't. If it's a multiple of two, we can write it like this:

2n

If it's NOT a multiple of two, than it must be one more than a multiple of two. That means we can write it like this:

2n + 1

Every integer can be expressed either as 2n or as 2n + 1.

Therefore, every perfect square can be expressed as either (2n)2 or (2n + 1)2.

Now, if you've studied a bit of Algebra, you hopefully know how to simplify both of those expressions:

(2n)2 = 22n2 = 4n2

(2n + 1)2 = (2n + 1)(2n + 1) = 2n(2n + 1) + 1(2n + 1) = 4n2 + 2n + 2n + 1 = 4n2 + 4n + 1 = 4(n2 + n) + 1

Notice the result! The first possibility gives us a multiple of four, and the second one gives us one more than a multiple of four! And since that covers every perfect square, we can conclude that all perfect squares are either a multiple of four or one more than a multiple of four!