Ask Professor Puzzler

Do you have a question you would like to ask Professor Puzzler? Click here to ask your question!

In our previous blog post, we were answering the question "Why is it useful to write complex numbers in trigonometric form?"

We saw how squaring a complex number can be simplified using trig, and we saw the same thing is true for multiplying any two complex numbers. In this blog post we'll explore how trigonometric form for complex numbers can help us take roots (cube roots, fourth roots, etc).

Before we get into taking roots of numbers, I'd like to point out something that you might not have realized: there are an infinite number of ways to write a complex number in cis form, because cos and sin are periodic functions:

rcis(xº) = rcis(xº + 360º) = rcis(xº + 720º) = etc.

Okay, tuck that information away in your memory banks; we'll get back to it shortly. Now let's talk about taking a cube root.

Let's suppose we wanted to take the cube root of the number 8...

"Well, that's silly," you might argue, "I already know the cube root of 8. It's TWO!"

Ah...but you only think you know. Bear with me, and I'll show you something interesting.

How would you write 8 as a complex number? It's 8 + 0i. Which is the same as 8cis0º. Now we know from the previous post, that if rcisx cubed equals 8cis0º, then r3 = 8, and 3x = 0º. Or, since it's the same value, 3x = 360º, or 3x = 720º.

Thus, x = 0º, x = 120º, or x = 240º.

Therefore, the cube roots of 8cis0º are 2cis0º, 2cis120º, and 2cis120º.

But what are those numbers?

Well, 2cis0º is easy; it's just 2 + 0i = 2. "Ah ha!" you might say, "I told you it was two!"

Very good, but let's keep going:

2cis120º = 2cos120º + 2isin120º = -1 + 1.732i

2cis240º = 2cos240º + 2isin240º = -1 - 1.732i

So it turns out that 8 has three cube roots, and you found them using trigonometry!

It turns out that you could have found those roots algebraically, by setting up the following equation:

x3 = 8

x3 - 8 = 0

(x - 2)(x2 + 2x + 4) = 0

So either x - 2 = 0 or x2 + 2x + 4 = 0

The first equation gives us the root we expected: x = 2.

The second equation can be solved using the quadratic formula:

x = (-2 +/- 3.4641i)/2, which simplifies to:

x = -1 + 1.732i or x = -1 - 1.732i

We obtain the same result algebraically as we did using trigonometry. You might argue that it was easier to use the algebraic method, but that's only because you know how to factor x3 - 8, and the factors are a linear factor and a quadratic. But suppose I'd asked you to find the fifth root of 32...what would you have done then? Or what if I'd asked you to find the cube root of 1 - 2i?

In these cases, algebraic solutions would be much more challenging, and the the trigonometry solution simplifies the process significantly.

This is a follow-up post to yesterday's "What is CIS Notation?" post. In this post we explore why it is useful to write complex numbers in their trigonometric form. Here you will find reference to the trigonometric double-angle formulas, and sum-of-angle formulas. If you're not familiar with these, you'll just have to take our word for those steps!

Let's start with a complex number in trigonometric form: 4cis(30º). If we were to write this number out without using the "cis" shorthand, it would look like this:

4[cos(30º) + isin(30º)]

This evaluates to approximately 3.4641 + 2i

Now supposing we wanted to square this complex number. You know the process, right?

(3.4641 + 2i)2 =

(3.4641 + 2i)(3.4641 + 2i) =

12 + 6.9282i + 6.9282i - 4 =

8 + 13.8564i

Let's do the same thing, but using the trig form for the complex number.

{4[cos(30º) + isin(30º)]}2 =

4[cos(30º) + isin(30º)] · 4[cos(30º) + isin(30º)] =

16[cos2(30º) + isin(30º)cos(30º) + isin(30º)cos(30º) - sin2(30º)] =

16[cos2(30º) - sin2(30º) +2isin(30º)cos(30º)] =

Now here's where those double-angle formulas come in:

cos(2x) = cos2(x) - sin2(x)

sin(2x) = 2sin(x)cos(x)

Thus, our expression can be simplified to:

16[cos(60º) +isin(60º)] =

16cis(60º)

Do you see what just happened there? When all is said and done, we ended up squaring the magnitude, and doubling the angle, and that was it!

As another example, let's take the complex number that we used in our previous blog post: 3 + 4i. If you wanted to square this, you would multiply it out as follows:

(3 + 4i)(3 + 4i) =

9 + 12i + 12i - 16 =

-7 + 24i

On the other hand, if we had the angle in cis notation: 5cis(53.16º), we can square the complex number by squaring the magnitude, and doubling the angle:

5cis(53.16º) = 25cis(106.32º), and we're done, just like that! That was a LOT quicker!

And, incidentally, this works for any cubing, raising to the fourth power, etc. To raise a complex number to the nth power, raise its magnitude to the nth, and multiply its angle by n. Now that's "power"ful!

But suppose we aren't squaring a complex number - suppose we're multiplying two different complex numbers? What happens then?

Let's make this very general; we'll call the two complex numbers r1cisA and r2cisB. Their product is:

r1(cosA + isinA) · r2(cosB + isinB) =

r1r2(cosAcosB + icosAsinB + isinAcosB - sinAsinB) =

r1r2[(cosAcosB - sinAsinB) + i(cosAsinB + sinAcosB)] =

r1r2[cos(A + B)* + isin(A + B)*] =

r1r2cis(A + B)

* sum of angle formulas were used to obtain this result.

Wow! Isn't that a great result - to multiply two complex numbers, you multiply their magnitudes and add their angles! That's easy!

But the real power (that was a double pun, by the way) of this way of writing complex numbers is in taking roots of numbers.

And that, I think, will become the topic of one more follow-up blog post!

B. from Vermont wants to know what "cis" notation is, how it works, and why it's useful.

"cis" is a shorthand way of writing complex numbers. Let's talk for just a minute about what complex numbers are. If you're already familiar with complex numbers, you can skip to the next section.

Complex Numbers

A complex number is a number which is made up of two parts. The first part is called the "real" part, and it is a real number (any of your normal counting numbers, zero, negatives, fractions, radicals, etc.) and the second part of the number is a real number times i.

i, in case you don't know, is the square root of negative one. "But," you might protest, "that's not a real number!" That's correct. In a very literal sense, by definition, it is not a member of the set of Reals.

So a complex number looks like this. a + bi. We call the "a" the "real part" and "b" is the "imaginary part."

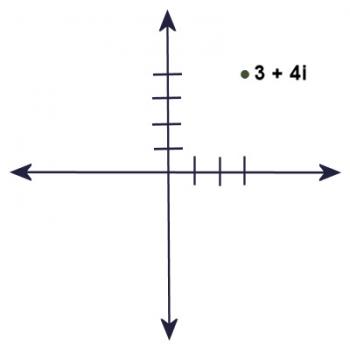

Graphing Complex Numbers

Obviously, you can't graph a complex number on a number line, since the number line contains only Real numbers. However, if you take two number lines and put them at right angles to each other, so that they cross on their zeroes, you can now graph a complex number. You use the horizontal number line to measure off the real part, and you use the vertical number line to measure off the imaginary part.

So, for example, to graph the point 3 + 4i, we would count three units to the right, and 4 units up. It's the same process we would use to graph the ordered pair (3,4) on a cartesian plane.

Similarly, -3 +4i would be graphed like this: count three units to the left, and four units up.

Magnitude and Angle

I don't know if you've ever thought about this, but if you're graphing points on a cartesian plane, every point can be described with an x and y, but there is another way to describe the point. You can describe it using a magnitude and an angle.

The magnitude is its distance from the origin (0,0), and its angle is the angle it makes with the positive x axis.

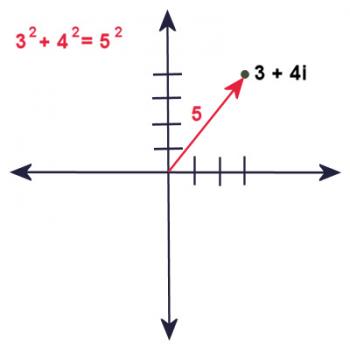

In the same way, every complex number can be described using a magnitude and angle. Let's consider the complex number 3 + 4i.

How far is that point from the origin? Well, it's three units right and four units up. Using the Pythagorean Theorem (or the distance formula, which is basically the same thing), we find that its distance from the origin is the square root of (32 + 42), which is 5 units.

so r = 5.

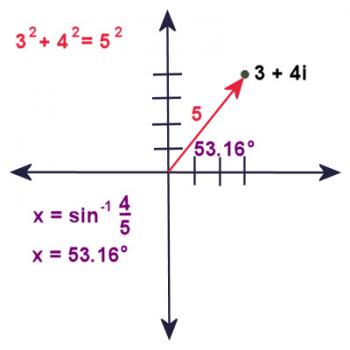

But what about the angle? Well, if you've done some trig, you'll figure out that the angle is sin-1(4/5), which is approximately 53.16 degrees.

In the same way, you could find an angle and radius for every complex number on the plane.

CIS Notation

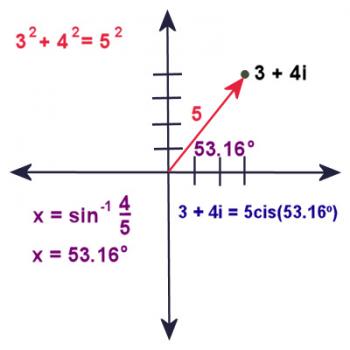

But wait a minute! Doesn't that mean we can write 3 + 4i like this: 5(cos(53.16º) + isin(53.16º))?

As a matter of fact, it does mean that. Every complex number can be written in the form r(cosx + isinx), where r is the complex number's magnitude, and x is its angle.

Mathematicians are notorious for not wanting to write everything out longhand, so, cosx + isinx gets simplified to CIS, which stands for "Cosine i Sine".

So 3 + 4i can be written as 5cis53.16º

That, hopefully, will answer your question "What is cis notation?" CIS notation is a shorthand way of writing complex numbers using its magnitude and some trig functions.

After school one day last week, one of my students wanted a little help with some problems she was working on. One of the problems was a system of two equations in two unknowns:

x2 + xy = 30

xy + y2 = 6

I said to her, "I like problems like this. I don't know right off the top of my head the best way to start it, and that means it's an interesting problem!" I asked her what she had tried.

She said, "I multiplied the second equation by -1, and then I added it to the first equation, to get rid of the xy term."

x2 + xy = 30

-xy - y2 = -6

------------------

x2 - y2 = 24

"That's good," I said. "So what next?"

"I don't know," she said, "that didn't seem to get me anywhere."

I said, "Okay, well, let's leave that there; we may want it later." So I put a box around it, to make sure I wouldn't erase it from the board. "Did you try anything else?"

"I couldn't think of anything else to try."

"Did you try adding the equations?"

"But nothing will cancel if I do that..."

"Try it anyway. I think something interesting will happen. I'm not sure it'll be USEFUL, but it'll at least be interesting," I said.

We did the equation addition:

x2 + xy = 30

xy + y2 = 6

------------------

x2 + 2xy + y2 = 36

It didn't take her long to notice that the left side could be factored:

(x + y)2 = 36

"And what does that tell us?" I asked.

"x plus y is either 6 or -6."

"That's great," I said, "you've just turned this into two problems!" So I drew a chart showing the two choices:

Choice One: x + y = 6

Choice Two: x + y = -6

"Now, I said," let's go back to your first equation that you came up with. Can you think of anything you can do with it?"

She realized she could factor the left hand side:

x2 - y2 = 24 ⇒ (x - y)(x + y) = 24

At this point she was getting a little excited about the problem, because it was starting to fall apart quite nicely. After all, if x + y = 6, then (x - y)(x + y) = 24 is equivalent to (x - y)(6) = 24, or x - y = 4. Similarly, if x + y = -6, then (x - y)(-6) = 24, or x - y = -4.

Now we find that we have two systems of equations:

Choice One: x + y = 6 and x - y = 4

Choice Two: x + y = -6 and x - y = -4

Both of these systems can be quickly solved (my student did them both in her head), to obtain the solutions (5, 1) and (-5, -1).

And the best part of my teaching day was hearing these words: "That was FUN!"

Then I showed her how the Teacher's Manual suggested doing the problem. Solve one of the equations for a variable:

x = (6 - y2)/y, and then substitute that into the second equation. I showed her the full solution. It was UGLY.

"I like our method better! Ours was fun!"

I understand the reasons for teaching the method that's in the text book; it's straightforward (even though it's ugly), and will work on a variety of problems. In addition, using that method gives students practice on a few different topics such as fractions and squaring binomials, etc.

We had no guarantee, when we first started the problem, that our ideas of subtracting and adding the equations were going to get us anywhere useful. As I said to the student, "We might try a bunch of things before we find something that works, but sooner or later we'll hopefully stumble on something useful."

But that's what problem solving is. Problem solving is not just using a rote method that a textbook shows you. It's looking at a problem and not knowing where to go, but being willing to try things to see what will happen. It's adding two equations together because you notice that adding them creates a perfect square, and that might be useful. It's subtracting two equations because you notice that it eliminates an xy, and that might be useful too.

It's a labyrinth of possibilities, with no guarantee that the things you try will be useful, but with the hope that somewhere there's a path that leads to a solution.

And, in the end, it's the delight of watching a system of quadratic equations disintegrate into pieces that you can solve in your head. It's the spark of excitement when the solution starts to dawn in a student's mind.

And it can be FUN!

Someone told me that on the Richter Scale for earthquakes, adding 1 gives an earthquake 10 times as big. Question 1: is this true?

Then they told me that adding 0.5 does not give an earthquake 5 times as big. Question 2: is that true, and why?

Doreen

Hi Doreen,

To both of your questions, the answer is "Yes."

The Richter Scale is called a "logarithmic" scale, which - for our purposes - just means that a 4.0 earthquake is 10 times as "big" as a 3.0 earthquake. And if you go from a 4.0 earthquake to a 6.0 earthquake, that's an earthquake 100 times as big (multiply by 10 to get to 5.0, and multiply by 10 again to get to 6.0).

("bigness" of an earthquake has to do with the amplitude of its seismic waves).

Regarding your second question, it is tempting to think that if a change of 1 means "ten times as big," a change of 0.5 means "five times as big." But it doesn't work that way.

Let me show you why. Let's talk about a 3.0 earthquake, a 3.5 earthquake, and a 4.0 earthquake.

You know that if you go from a 3.0 earthquake to a 4.0 earthquake, that's 10 times as big.

But if a change of 0.5 meant 5 times as big, then we'd calculate:

From 3.0 to 3.5 is 5 times as big;

From 3.5 to 4.0 is 5 times as big;

Therefore, from 3.0 to 4.0 is 5x5 = 25 times as big! That's not right!

So let's just break down the math a bit.

If you want to go from a Richter scale reading of x to a Richter scale reading of y, you would take the difference of x and y, raise 10 to that number, and that's your "bigness" ratio.

For example, if you wanted to go from 2.0 to 7.0, your ratio is 107-2 = 105 = 100,000.

So let's talk about a Richter Scale difference of 0.5:

Suppose you wanted to go from 2.0 to 2.5. Your ratio is 102.5 - 2 = 100.5. What is 100.5? It's the square root of 10, which is approximately 3.1623.

So if one earthquake has a Richter value of 4.0, and another had a Richter value of 4.5, the 4.5 earthquake is 3.1623 times as big as the 4.0 earthquake.

By the same reasoning, we could figure out how much bigger a 4.2 earthquake is compared to a 4.1 earthquake:

104.2 - 4.1 = 100.1 = 1.2589.